Art historian Lee Sandstead has a dirty little secret: many of the

paintings he had been taught to admire when a student, were

disappointments when he saw them in person. This is by no means a

condemnation of the artists who painted the works, nor of Sandstead's

teachers for lavishing praise upon these paintings. It is just that

whenever Sandstead encountered these pieces in museums, he noticed that

the elements which had originally made the paintings special were

missing or obscured. The problem he found was that many artworks are in

need of a good bath.

“This

might

sound

rather

incredible,”

says

Sandstead,

“but

most

classic

paintings

in

a

museum

need

some

kind

of

conservation,

such

as

replacing

the

varnish.

And

even

more

incredible,

in

all

of

my

art

history

classes

that

I

have

ever

taken,

no

professor

had

ever

mentioned

this

very

basic—yet

crucial—fact.”

Sandstead's quest to see paintings as they were "intended to be seen" began with Leonardo daVinci's La Giaconda (the Mona Lisa). When he first saw it in its current state, he was . . . underwhelmed. “I

sat

there

looking

at

this

very

small

and

dark

painting

behind

three

inches

of

bullet-proof

glass

scratching

my

head

in

puzzlement.

Where

were

her

eyebrows?

Why

is

she

so

yellow?”

He knew from the account of Giorgio Vasari, who described La Giaconda in 1547, that there was once something more to the painting:

In this head, whoever wished to see how closely art could imitate nature, was able to comprehend it with ease; for in it were counterfeited all the minutenesses that with subtlety are able to be painted, seeing that the eyes had that lustre and watery sheen which are always seen in life, and around them were all those rosy and pearly tints, as well as the lashes, which cannot be represented without the greatest subtlety. The eyebrows, through his having shown the manner in which the hairs spring from the flesh, here more close and here more scanty, and curve according to the pores of the skin, could not be more natural. The nose, with its beautiful nostrils, rosy and tender, appeared to be alive. The mouth, with its opening, and with its ends united by the red of the lips to the flesh-tints of the face, seemed, in truth, to be not colours but flesh. In the pit of the throat, if one gazed upon it intently, could be seen the beating of the pulse. And, indeed, it may be said that it was painted in such a manner as to make every valiant craftsman, be he who he may, tremble and lose heart.¹

What then was Sandstead missing? Though he had not been taught the fact

in school, he soon realized that for paintings, classical paintings, to

be understood, several items were needed: the removal of centuries of

dirt and grime, the removal of yellowed and aged varnish, the addition

of a new varnish to bring out the colors and increase the depth of the

darks, and some good, controlled lighting in which to view the works.

As Sandstead says, ". . . before you can understand an artwork. . .

(its) characters, symbols, messages, themes, etc., you first have to

know what you are looking at."

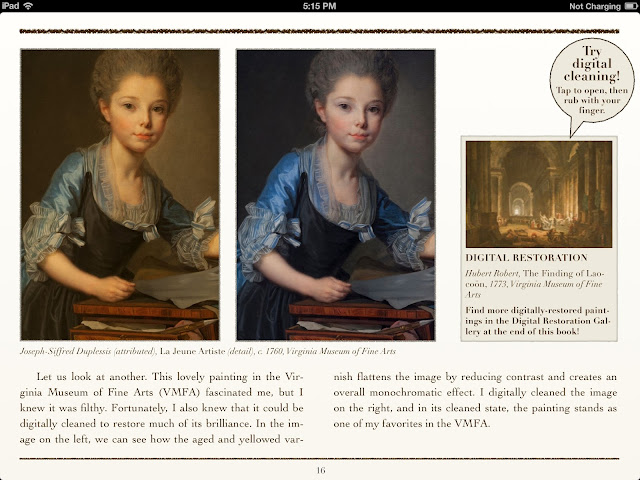

Searching out works in museum's throughout the world, Sandstead, a

talented a photographer in his own right, began taking pictures of

paintings in need of cleaning, and correcting them digitally so he could

appreciate the works as they were intended to be viewed.

Now, Sandstead, whose TV show on The Travel Channel, Art Attack with Lee Sandstead,

revealed the man to be "the world's most fired-up art historian," is

trying to educate the public about what they should be seeing, at least

superficially, when they look at a painting. Using new technology built

upon Apple's iBook Author, Sandstead teamed up with app company Tapity

to release a new, interactive book, Cleaning Mona Lisa, available today at the iTunes store.

In it, Sandstead describes his disappointment with certain works which

were not being presented at their best in museums, and shows examples

of how some works would look if they were restored and lighted properly.

His audience is not intended to be artists, but the general public– most

artists should already know that many paintings in museums have been

damaged by age. As such, though, it is very encouraging. Sandstead's

presentation is clear and simple, and his energy has the chance to

encourage more people into museums. More importantly for contemporary

realists, Sandstead has a sympathy for indirect painting methods, and is

eager to educate his readers in the differences between classical and

modernist technique, and why they should be appreciated differently.

Cleaning Mona Lisa is available for iBooks2 on the iPad. It can be purchased on iTunes for $2.99. For more information, visit Sanstead's website.

¹Vasari, Giorgio, "Life of Leonardo da Vinci", in Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, translated by Gaston DeC. De Vere, (London: Philip Lee Warner, 1912-1914).

courtesy:underpaintings/