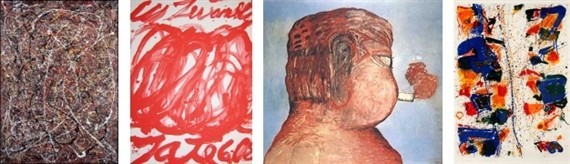

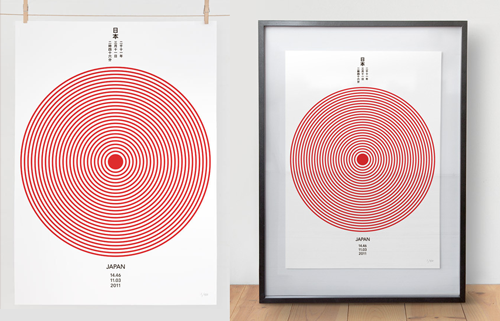

Before beginning to read this article, please look at the images above. Which was drawn by a child and which by a well-known Abstract Expressionist? The answer lies a few paragraphs down.

How often have you heard people describe artworks by artists such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko or Cy Twombly as drawings that a 5-year-old child could have made? The answer is probably, very often. But is this true? Can children produce art whose perceived quality, as least by widespread artistic circles, matches that of renowned artists who sell their art for millions of dollars?

Boston College psychologists Angelina Hawley-Dolan and Ellen Winner's research, recently published in the journal Psychological Science, seeks to answer this question. When comparing artworks created by a child or even a monkey to that of an acclaimed artist, whether non-aficionados like a particular artwork or not, they can usually identify it as the product of human creativity.

To further understand this study and its significance on our aesthetic behavior, MutualArt.com spoke with Hawley-Dolan about how people evaluate the skill in those who paint or sculpt non-representationally.

Here's the answer to the question: The image on the left was drawn by 4-year-old Jack Pezanosky. The image on the right shows a work by Abstract Expressionist Hans Hoffman.

What led you to research this and what significance does it play in psychology?

We began by asking ourselves - how do people evaluate abstract art, "pictures of nothing"? People have little difficulty judging the skill of artists who make representational paintings, but evaluating skill in those who paint or sculpt non-representationally is far more subjective. Works by 20th century Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, or Cy Twombly have often been likened -- sometimes pejoratively, sometimes positively -- to children's paintings. Though critics such as Michael Kimmelman of the New York Times assert that the scribbles of Twombly are distinct from those made by children, the superficial similarity between abstract expressionist works and markings by preschoolers has led to embarrassing confusions. For example, in 2007, 5-year-old Freddie Linksy duped the art world into paying large sums for his ketchup paintings. In 2005, three paintings by chimpanzee Congo sold for over $25,000 each -- fetching more than did paintings by Warhol or Renoir.

You ask what the significance of this research is for psychology. Psychologists attempt to understand all aspects of human behavior. Aesthetic behavior is universal and goes back to the earliest humans. This research shows that even people untrained in art can recognize that abstract art (so often disparaged as meaningless and without skill) has intention and planning and thought behind it that distinguishes it from the superficially similar scribbling of children and animals.

What were your hypotheses?

1. In all conditions (no label, correct label, and incorrect label) we predicted that both art students and non-art students should choose professional works at an above-chance level in response to both the judgment question (which one is the better work of art) and the preference question (which one do you prefer). We reasoned that even though people think that works by abstract expressionists are indistinguishable from those by children and nonhumans, in fact, differences can be perceived, people see more than they think they see, and works by professionals are more highly valued.

2. That works should be chosen more often in response to the judgment than the preference question because judgments of quality should be responsive to perceived skill, whereas preferences are more idiosyncratic.

3. Compared with non-art students, art students should choose the professional works more often in response to both the judgment and the preference questions, because of art students' presumably greater experience analyzing images. They should also be more likely than non-art students to show consistency between preferences and judgments because their preferences should emerge from their analyses of the works.

4. Labels should affect judgments more than preferences. Correct labels should increase the frequency of choosing professional works in response to the judgment question, but incorrect labels should fail to depress such choices.

Artworks by (from left) Jackson Pollock, Cy Twombly, Philip Guston, Sam Francis

Please describe the methodology.

We paired 30 abstract paintings by famous artists with superficially similar paintings by children or animals (monkeys, chimps, gorillas, elephants) and asked people which they preferred and which they thought was better art. To find out if it mattered whether people knew who had made the works, we presented the first set of images without labels, and the rest with either correct (monkey as monkey, artist as artist) or reversed (monkey as artist, artist as monkey) labels. Half of the participants had no art training; half were trained in studio art.

Images of which artists did you select and why?

The professional works we chose for our study were painted during the Abstract Expressionist movement (which entered New York City beginning in the mid to late 1940s). We included the following artists in our experiment:

Karel Appel

Gillian Ayres

James Brooks

Elaine de Kooning

Sam Feinstein

Sam Francis

Helen Frankenthaler

Philip Guston

Hans Hoffman

Franz Kline

Morris Louis

Joan Mitchell

Kenzo Okada

Ralph Rosenborg

Mark Rothko

Charles Seliger

Theodoros Stamos

Clyfford Still

Mark Tobey

Cy Twombly

We chose these artists to represent our abstract expressionists because they are among the most famous artists of this movement. We chose artworks that were entirely non-representational and that were representative of the artists' styles, but not their most famous works.

By which attributes did you match the paintings?

We matched the paintings with a team of artists and psychologists. We matched the paintings by attributes such as similarity in color, medium, line quality and brushstroke. Images had to be similar in at least two of these categories. We matched these in a holistic, qualitative way.

What are some of the most interesting results?

Turning to the results, all participants preferred and judged as better the artists' works at a level significantly above chance. Thus, despite the common cliches of the cynics, people can see the difference! Second, labels had only a minimal influence. Art students were completely unaffected by labels - their responses were the same no matter which labeling condition; undergraduates untrained in art were influenced by labels only when asked for their judgments. Correct labels boosted their choice of artist for "which is the better work," but most interestingly, reversed labels did not depress their choice of artists' works below chance. That is, they resisted choosing the animal/child works even when these were falsely labeled as by an artist! Third, and importantly, when people selected the artists' works, they were far more likely to justify this choice by referring to the mind behind the art than when they chose works by children and animals. Thus when selecting a painting by abstract expressionist Mark Rothko, they said that the work looked intentional and planned; when selecting a child or animal work, they said that the liked the colors or brush strokes.

What is your analysis of the results?

We conclude that we know more about abstract art than we think; we recognize the mind behind the art; and the world of abstract art is more accessible than we realize. If we were to speculate about why and how people can tell the difference our reasoning would be the following:

In abstract expressionist paintings, the appearance of realistic objects is entirely neglected: the style (use of color, space, figures) becomes the content of the piece. The art historian William Chapin Seitz points out that an abstract expressionist's style is created by the process by which the paint is applied, the formal elements of the composition, and the relationship of the elements (Seitz, 1983). In addition, he comments, "nonobjective painting, like that of the primitive, is built directly of lines, strokes and areas."

A commonly heard claim is that the works of Abstract Expressionists look much like the scribbles and finger-painting of young children (see the film, My Kid Could Paint That). In addition, people have been deceived into spending lots of money on paintings by a chimp (which are of course non-representational) thinking that the work was by a rising abstract expressionist. But our study shows that people can, in fact, tell the difference between a child's lines and strokes and those in a work by an abstract expressionist - if the two works are paired side by side. And this is NOT due to recognizing the different materials that a child might use vs. a professional artist, because our images were presented on a computer screen, and it was not possible to determine whether the colors were from cheap poster paints on newsprint or fine oil paints on canvas.

The finding that people were much more likely to talk about seeing intentionality, planning and "mindfulness" in the professional than in the child or animal paintings shows us that people are perceiving, perhaps unconsciously, the difference in the mind of the child/animal vs. the mind of the professional artist.

If you think about it, this makes a great deal of sense. Let's consider the statement by abstract expressionist painter Hans Hofmann who said that art is "The ability to simplify means to eliminate the unnecessary so that the necessary may speak" (Hess, 1952). This statement indicates how much deliberation goes into an abstract painting (clearly considerably more than what a child or chimp would engage in). Mark Rothko's use of color layering is not random: it is patterned and planned. So are the drips of a Jackson Pollock. Hans Hoffman's book Search for the Real discusses the "push/pull color theory" where spatial dynamism is created not only by lines and shapes, but also by the interplay of light, color, space and shape. The spatial relationships among all these aspects create visual intrigue, volume and even movement. These tensions create a visual story, or a visual language. In short, as any artist or art historian knows, abstract expressionists were deliberately experimenting with spatial relationships, color tensions and pictorial structure.

By recognizing more planning and intentionality in the professional artworks, participants were able to recognize a "visual language" or artistic "footprint" within the content of the artworks made by professionals (in contrast to the more random markings made by children, apes, and elephants). What we are seeing in this study is that people are, perhaps unconsciously, picking up on this visual genre of art as having a structure, a method. People can pick up on the interplay of space, color and shape that Hoffman describes. People are responding to the fact that there are some images, out of all the images we show them, that have a pattern, expression, a visual language, even an intonation that the other images (child, monkey images) do not. While we might like one style, or "language" better than another, we can see and detect a structured visual language in the professional works. The people in our study saw the deliberations of the artist's mind.

Written by MutualArt staff